Ferrante Fever

Event report

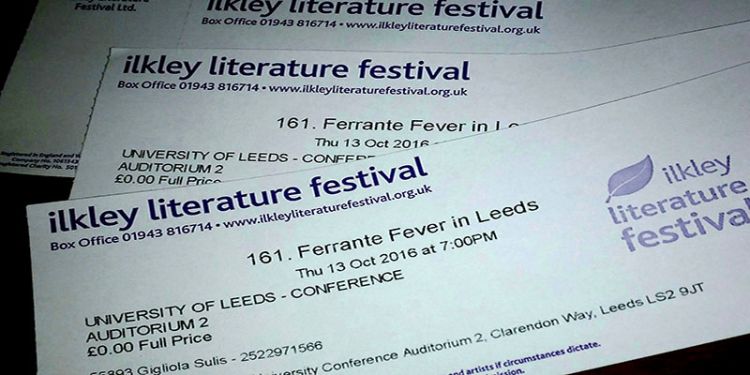

Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan quartet has caused, what can only be described as a ‘fever’, through the UK. Leeds is no different from the rest of the country, holding our very own ‘Ferrante Fever’ event that took place on the 13th October. We were privileged to have a panel of speakers closely associated with Ferrante and her publishing house. Led by organiser Olivia Santovetti we were introduced to Ann Goldstein, now one of the most famous international translators thanks to her translations of Ferrante’s four novels, Tiziana de Rogatis an associate professor of Italian and Comparative Literature at the Universita’ per Stranieri di Siena, Daniela Petracco director of Europa Editions and Thea Lenarduzzi commissioning editor for the Times Literary Supplement and author of the blog ‘Ferrante Fever’.

Most ironically, days before the event Elena Ferrante’s true identity was supposedly revealed to us – the panel however were unwilling to vouch for the authenticity of these claims not knowing themselves who the real Elena Ferrante really is. Likewise, for everyone in the audience it was clear that the name of the author changes nothing in regards to our love of the Neapolitan series.

However, it is the anonymity of the author that has been at the crux of the novels. The content of which is free from the binds of authenticity. We are the privileged reader that can relate to the stories because they relate to us, to all types of readers – from those who read a lot to those who read once or twice a year. It is no surprise therefore that such a ‘fever’ is created – we are by nature nosy and want to know what happens next to Elena Greco, the protagonist, and her brilliant friend Lila Cerullo. We read on and on, with each book effecting the reader differently, a truly introspective experience.

As well as anonymity, Naples as a setting for the quartet was discussed by the panel. I visited Naples myself after reading Ferrante’s novels and found it to be everything she had touched upon and more. Ferrante depicts the ‘true’ Naples in a unique way. It is not stereotyped, but shown for what it really is – a working class city with a steel industrial centre. Ferrante may name certain piazzas or streets but nothing is every fully described, which allows room for the readers own imagination and questioning. For example, are the city’s deeply rooted traditions for better or for worse in the face of the burgeoning modernity?

Most important was the discussion about language and dialogue. Ann Goldstein has been translating Ferrante’s work for the last 30 years. Her ability therefore, to catch every nuance and subtly of language and leaving nothing ‘lost in translation’ is undeniable. Interestingly, Ferrante supposedly prefers a rough style of writing. There is emphasis consequently on the importance of imperfection, giving the text greater authenticity and readability.

Language itself is a prominent theme in all four novels. The use of the Italian language by Greco in intellectual dialogue signifies her rejection of Naples and search for academic acclaim. The Neapolitan dialect for Greco has an aspect of dirtiness and is associated to violence and crime, all of which she is determined to distance herself from by achieving a higher intellect. But is language a saviour to the women in Ferrante’s text? When Greco returns to Naples many years later, after forging a career for herself, she feels lost, estranged from her own language and indeed mocked by her words that she once used as a form of assertiveness. It appears that Ferrante draws our attention not only to desires and aspirations but recognition of our own origins.

It is hard to summarize a discussion full of such interesting thoughts and ideas relating to the Neapolitan series. Three points, however, stood out for me the most. made by members of the audience as well as the panel. Significantly, Elena Ferrante is a female writer, with a female protagonist, both of which are writing about and commenting on a country in which women count for less. I think this really highlights the importance of Ferrante’s text not only to Italian women but all women. Secondly, the texts exemplify the difficulty of being both a mother and a woman, further heightening the relatability of Ferrante’s books and amplifying her readership. Lastly and most poignantly, it is a story about friendship in which the best friend is the person who you so want to be and yet also the person you dread to be.

If you have not read Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan series yet I encourage you to do so, once you begin you will undoubtedly join the Ferrante Fever.

Freya Pelissier, final year student in English and Italian, 13 October 2016.