Research project

Maternal mortality in East Africa

- Start date: 1 February 2018

- End date: 31 January 2023

- Funder: Global Challenges Research Fund; University of Leeds Economic and Social Research Council Impact Acceleration Account

- Primary investigator: Shane Doyle

- Co-investigators: wthjep

- External co-investigators: Professor Wenzel Geissler (University of Oslo/University of Leeds), Dr Benson Mulemi (Catholic University of East Africa/University of Pretoria), Dr Saudah Namyalo (Makerere University)

Description

Why is maternal mortality so high in Africa? In 2020, the risk of dying due to maternity-related causes was 268 times higher for women in Sub-Saharan Africa, compared to Western Europe (source: Unicef). Most maternal deaths are preventable, and our research focused on the human factors which contributed to problems such as miscommunication, mistrust, and delay in seeking or providing treatment.

To understand the interconnected social and cultural causes of maternal death, this project adopted an interdisciplinary approach, and concentrated on the region of western Kenya. Kenya has one of Africa’s highest Maternal Mortality Ratios (530 per 100,000), and within Kenya the western counties of Kisumu and Siaya have particularly high levels of maternal death.

Find out more in an article written at the beginning of the project: ‘East Africa’s high maternal death rate’, on the University of Leeds Medium website.

Research findings

Maternity and Relationships

Our research began by seeking to understand why pregnancy, childbirth, and the post-natal period in western Kenya were so frequently associated with conflict, anxiety, and neglect.

Jane Plastow’s use of participatory theatre shed new light on the tensions surrounding maternity. Women, by acting out key experiences, were able to reveal the enduring emotional impact of past traumas, and draw out the interpersonal aspects of maternal health problems.

Follow-up interviews and archival research explored key insights from this initial participatory research further, examining the evolving role of grandmothers and mothers-in-law in the field of maternal health, and tracing the historical development of stigma surrounding pregnancy among teenage and ‘geriatric’ mothers, and among poor and uneducated women.

Maternal Health Miscommunication

A series of obstacles to the transmission and reception of maternal health information was revealed by Saudah Namyalo’s linguistic research.

Whereas health communication in East Africa in the era of decolonisation had focused heavily on the use of vernacular languages and concepts, by the 2010s medical information in Kisumu and Siaya was typically provided in the English language. While research participants attended ante-natal clinics, they often did so unwillingly, and most sought alternative maternal health guidance in their vernacular language from non-clinical sources.

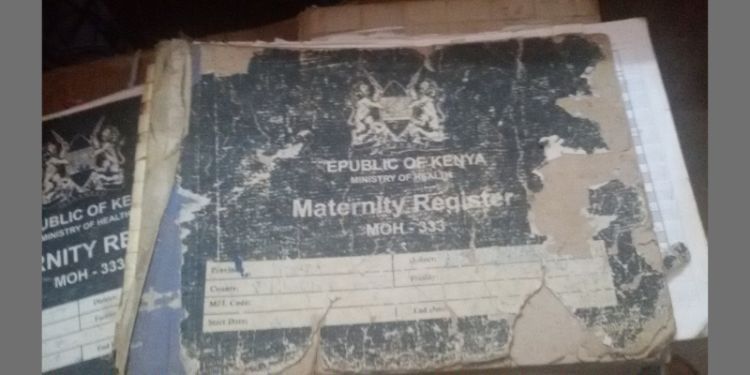

The Institutionalisation of Childbirth

Maternal health services were marginalised within post-colonial medical systems until the 2000s, when global metricisation and targets highlighted how far Africa’s Maternal Mortality Ratios had diverged from those of the wealthiest nations.

In order to achieve the UN’s Sustainable Development Goal for maternal health, the Kenyan government sought to ensure that all deliveries were supervised by clinically-trained personnel, which in effect required the institutionalisation of childbirth. Rather than lead to the disappearance of the Traditional Birth Attendant, this process has instead seen local midwives present themselves as providing respectful, sympathetic, and culturally-sensitive support to women before and after childbirth, heightening public criticism of what is perceived to be the impersonal, mechanistic nature of maternity services in the clinic.

Wenzel Geissler’s anthropological research examined how Traditional Birth Attendants repositioned themselves in relation to rapidly changing legal restrictions and market opportunities.

Respect and Self-Respect

When the anthropologist, Benson Mulemi, compared the encounter between staff and patients at ante-natal clinics with how patients behaved at home during follow-up interviews, he was struck by how the clinical relationship was so one-sided.

Pregnant women in their domestic setting asked many questions about their condition, and appeared confident and articulate. In the clinic, they received information, were subject to tests, but rarely did they pose questions nor themselves receive questions or explanations.

Interviews with staff and patients alike indicated that their relationship was commonly regarded as unequal, problematic, and, not infrequently, conflictual. Historical research examined the evolution of this discordance, drawing out the influence of missionary moralism, post-colonial nation-building, and a professional culture that valued endurance, self-sacrifice, and didactic, instructional expression.

Engagement and dissemination

This research relied on the long-term engagement and support of multiple community groups, governmental and non-governmental organisations, and medical providers from across the region. Its findings were shared in several formats, from plays and radio series to formal dissemination workshops.

The project culminated in a dissemination workshop held in January 2023. After this workshop, the head of the medical system in part of western Kenya invited the team to present to key policymakers in the region. The main findings of the project have been recommended for policy change in reproductive health in Western Kenya. Read more in ‘Social and cultural causes of maternal mortality in East Africa’, on the Leeds Social Sciences Institute website.

Talks

Publications

- Doyle, Shane, ‘Peer learning and health-related interventions: Family planning and nutrition in Kenya and Uganda, 1950–2019’, in Véronique Petit, Kaveri Qureshi, Yves Charbit, and Philip Kreager (eds), The Anthropological Demography of Health (Oxford University Press, 2020), pp. 127-150.

- Doyle, Shane, ‘Maternal health, epidemiology and transition theory in Africa’, in Megan Vaughan, Kafui Adjaye-Gbewonyo, and Marissa Mika (eds.), Epidemiological Change and Chronic Disease in Sub-Saharan Africa: Social and Historical Perspectives (UCL Press, 2021), pp. 106-32. This book is available open access.

- Doyle, Shane, ‘Grandmothers’ undesired autonomy: Social reproduction and histories of self-accomplishment in Western Kenya’, in Yvan Droz, Yonatan Gez, Marie-Aude Fouéré, and Henri Médard (eds.), Self-accomplishment in East Africa (Africae, forthcoming).

Find out more

Read a feature about this project on the University of Leeds Resarch and Innovation website.

Read more about this project on the UK Gateway to Research website.