The controversy of insulin and its Nobel Prize: 100 years on

Dr Kersten Hall explores the history of insulin and what it has taught us in this article, 100 years after Dr Banting's Nobel Prize Award.

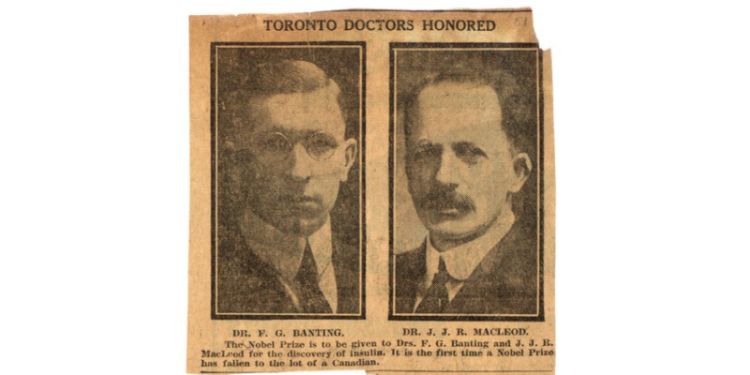

One hundred years ago, on the morning of October 25th, 1923, Canadian clinician Dr. Fred Banting received the phone call of which every scientist must secretly dream. On the other end of the line, an excited friend congratulated Banting on the news that he had just been awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine for his discovery of insulin. But Banting’s reaction on hearing that he had just received the most prestigious accolade in science was somewhat surprising to say the least. He was furious. Utterly livid, in fact.

Considering that his work would save countless lives (my own included), Banting’s response is perhaps even more surprising. Until the discovery of insulin, diabetes was a certain death sentence. Unable to make insulin, a hormone which is normally produced in the pancreas, diabetic patients could not use the sugar from their diet as fuel and so gradually slid into a fatal coma brought on by rising levels of toxic metabolic by-products called ketones in their blood. Doctors could only look on helplessly, unable to do anything other than put their patients on a starvation diet to delay the inevitable outcome.

Little wonder then that when insulin was first used to successfully treat patients in 1922, doctors were delighted. But for Banting, the sense of triumph did not last long. On hearing the news about the award of the Nobel Prize that October morning in 1923, he told his friend to ‘go to hell’, slammed down the phone receiver and checked the morning newspaper for confirmation of the story. Then, jumping into his car, he drove across Toronto in such a blind rage that one onlooker feared it would end in violence.

The success of insulin injections

The newspaper headlines confirmed Banting’s worst fear – the Nobel Prize had been awarded not just to him, but also to his boss, John James Rickard Macleod, Professor of Physiology at the University of Toronto. Banting hated Macleod and felt that he had no right whatsoever to have any claim on the discovery of insulin, let alone share a Nobel Prize for this achievement. Yet had it not been for Macleod offering him some space in his laboratory where he could explore his ideas to test the anti-diabetic effects of pancreatic extracts, Banting might very well have remained a struggling GP in provincial Ontario with a failing private practice and never have received that fateful phone call in the first place.

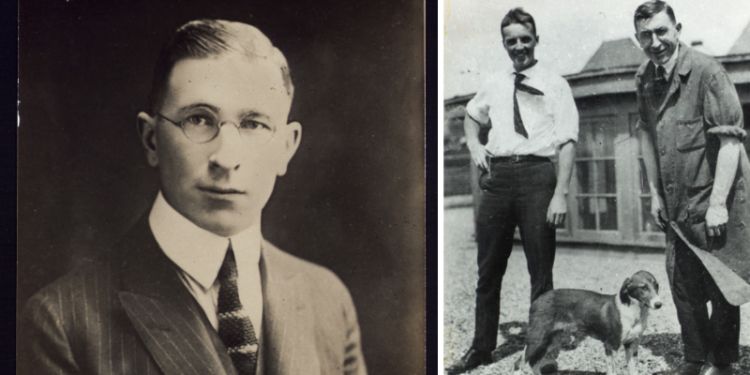

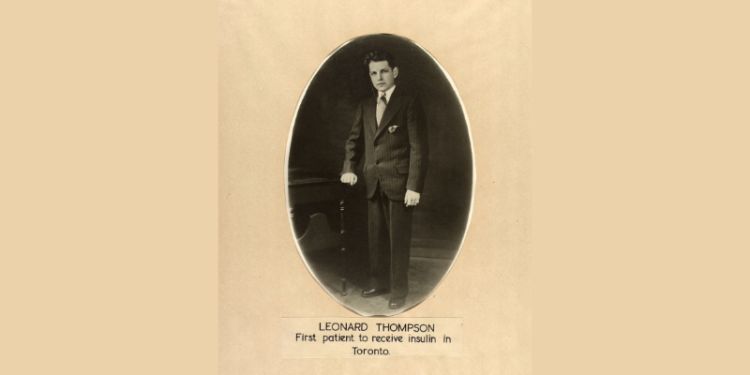

Having spent the summer of 1921 working in Macleod’s laboratory with final-year student Charles Best, testing the effects of pancreatic extracts on diabetic dogs, Banting had felt confident enough early in the following year to test his preparations on a human patient. But when 14-year-old Leonard Thompson was injected on 11th January 1922 with material prepared by Banting and Best, the result was not a success. Although the high levels of sugar in Leonard’s blood fell, he continued to produce poisonous ketones and suffered an adverse immune reaction due to impurities in the preparation.

Two weeks later, he was injected again with a fresh preparation which not only reduced his blood sugar levels but abolished the production of ketones and crucially did not trigger an immune response. So what had changed in those two weeks? The answer is that this second preparation had been made not by Banting and Best, but by their colleague, James Collip, a biochemist who had used alcohol to remove the toxic impurities and isolate insulin as the active agent.

Thanks to Collip’s procedure, Macleod made a public announcement in May 1922 of the discovery of insulin and the accolades began to flood in for Banting. He was awarded a pension by the Canadian government, received a Professorial chair and an invitation from King George V to join him for tea at Buckingham Palace. Then on 25th October 1923, came the phone call to tell Banting that he had been awarded the Nobel Prize which sent him into a rage.

Others claimed the prize

Nor was Banting the only person to be furious at this news. Several other researchers felt strongly that they had quite independently found pancreatic extracts to have an anti-diabetic effect well before Banting, and that they therefore had priority in the discovery of insulin. German clinician Georg Zuelzer even wrote angry letters of protest to the Nobel Committee arguing that, as early as 1908, he had not only used the anti-diabetic effects of pancreatic extracts to treat patients in Berlin but had also filed a patent on his method which recognised the importance of using alcohol to remove toxic impurities.

Perhaps the person who felt the most resentment was Banting’s colleague, Charles Best. After Banting’s death in a plane crash in 1941, Best sought to put this situation right. With Macleod having already died in 1935, the only surviving members of the original Toronto team were Best and Collip. Best was determined which of these two names the world would remember for their role in the discovery of insulin. As he rose through the ranks of the medical world in the years that followed, Best took pains to diminish Collip’s vital contribution and establish himself as the pivotal figure in the story of insulin.

Is insulin a miracle cure?

While controversy surrounded who should get the credit for its discovery, the newspaper headlines of the time were clear about one thing – that insulin was a miraculous cure for diabetes. Delighted as they were, diabetes clinicians knew that it was nothing of the sort. Having had Type 1 Diabetes myself for just over ten years, I think I know what they mean. In his book ‘Bittersweet: Diabetes, Insulin, and the Transformation of Illness’, the diabetes clinician and historian of medicine Chris Feudtner observes that insulin transformed what would have been an otherwise fatal condition into a chronic one that could now be managed – albeit with the potential for serious long-term health complications.

But when insulin was first discovered, Elliott Joslin, one of the most eminent diabetes specialists in North America, warned that it was a remedy “primarily for the wise and not the foolish, be they patients or doctors.” He said, “Everyone knows it requires brains to live long with diabetes but to use insulin wisely requires more brains.”

Joslin’s point was that a technological solution to a problem can only do so much. Certainly, daily injections with insulin are an absolute necessity for me to stay alive – but if I want to live well, these are not enough. Daily injections of insulin have to go hand in hand with responsible behaviour on my part with regard to such things as diet, exercise and lifestyle. I’ll readily confess, that this is not always easy or straightforward but its importance was underlined by Professor David Nabarro, the World Health Organization Special Envoy on Covid-19 who, when asked in an interview on Radio 4’s ‘Today’ programme about using tracing apps to manage the spread of Covid-19 during the pandemic, replied:

‘. . . that’s not going to be the total answer. The total answer is basically us, just coming to terms with the fact that we’re going to have to change our behaviour wherever possible. Physical distancing, face protection, protecting those who are most vulnerable, looking after the people who are in the front line who are getting infected all the time, like bus drivers or people in food processing plants.’

Whether managing Type 1 diabetes, or the spread of a viral pandemic, the lesson is the same – the technology, welcome as it is, can only do so much of the heavy lifting. The rest is down to us. This is why, as we face the inevitable challenges of future pandemics, the rise of AI and climate change, the discovery of insulin which earned a Nobel Prize one hundred years ago this month still has a lesson for us all, whether or not we happen to be injecting ourselves with it.

Written by Dr Kersten Hall, Centre for History and Philosophy of Science at the University of Leeds.

Dr Hall is the author of ‘Insulin – the Crooked Timber: A History From Thick Brown Muck to Wall Street Gold’ (Oxford University Press, 2022). His Twitter handle is @monkeynut_coat.

Image credits

Header image

‘Toronto Doctors Honored: Nobel Prize to Banting. Dr. J. J. R. Macleod also.’ October 1923; MS COLL 76 (Banting) Scrapbook 1, Box 2, Page 81; Insulin Collection, F. G. Banting (Frederick Grant, Sir) Papers. Reproduced courtesy of the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto. Online at https://insulin.library.utoronto.ca/islandora/object/insulin%3AC10111.

Body images

Photograph of Fred Banting (1891–1941) taken on December 27, 1922. Insulin Collection, F. G. Banting (Frederick Grant, Sir) Papers, Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto; MS COLL 76 (Banting), Box 63, Folder 3A. Reproduced courtesy of the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto. Online at https://insulin.library.utoronto.ca/islandora/object/insulin%3AP10042.

Photograph of Frederick Banting and Charles Best (1899–1978) with a dog on the roof of the Medical Building (August 1921). Insulin Collection, Best (Charles Herbert) Papers, Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto; MS COLL 241 (Best) Box 109, Folder 4. Reproduced courtesy of the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto. Online at https://insulin.library.utoronto.ca/islandora/object/insulin%3AP10077.

Photograph of James Bertram Collip (1892–1965) [ca. 1920]. Insulin Collection, Collip (James Bertram) Papers, Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto MS COLL 269 (Collip), Item 1. This photograph is reproduced from the original held by Barbara Collip-Wyatt. Reproduced courtesy of the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto. Online at https://insulin.library.utoronto.ca/islandora/object/insulin%3AP10005.

Formal photograph of Leonard Thompson. Insulin Collection, F. G. Banting (Frederick Grant, Sir) Papers, Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto; MS COLL 76 (Banting), Box 12, Folder 1. Reproduced courtesy of the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto. Online at https://insulin.library.utoronto.ca/islandora/object/insulin%3AP10046.