Deepfakes: has the camera always lied?

Fake footage is a centuries-old problem that began long before digital technology, according to a Leeds academic.

A new research paper, published in the philosophy journal Synthese, argues that deepfakes aren’t as unprecedented as they may seem, as photos and videos have been the subject of manipulation for more than a century.

Instead of seeing deepfakes as a sign of a digital apocalypse, philosopher Dr Joshua Habgood-Coote says we should be focusing on the insidious social problems behind the videos, such as misogyny and racism.

Dr Habgood-Coote, Research Fellow at the University of Leeds’ School of Philosophy, Religion and History of Science and author of the paper, said: “There’s been a lot of public debate about deepfakes, which has become increasingly apocalyptic, pushing the idea that reality and truth are being lost in a technological dystopia.

“We should think about deepfakes as a social rather than technological problem and focus on the way deepfakes will be used against marginalised groups.”

In recent weeks, deepfake images of Pope Francis wearing a puffer jacket and Donald Trump being arrested have flooded social media, with many showing telltale signs of digital manipulation, from extra limbs to distorted hands.

The camera lies

Photo manipulation didn’t begin with the release of Photoshop in 1990, but more than a century beforehand in the late 1800s.

Dr Habgood-Coote said: “The idea of a golden period in which recordings unproblematically represented the world is a fiction.”

The research highlights several examples of this:

- Famous photos in the 1860s claimed to capture real spirits, including the ghost of Abraham Lincoln. The photographer, William Mulmer, was accused of fraud, and after a sensational trial in 1869, a columnist for the New York World wrote: “Who, henceforth, can trust the accuracy of a photograph?”

- Footage of the Spanish-American war in 1898 involved widespread fakery, including staged cavalry charges and the use of toy boats to represent naval engagements.

- The New York Evening Graphic notoriously produced staged photos to illustrate current events between 1924 and 1932, often printing sexualised pictures of women.

- Until the 1980s, film and development processes were set up to accurately depict white skin only, often changing the skin tones of anyone with darker skin to hide their faces in artificial shadows.

Social vs technological

Dr Habgood-Coote argues that, because deepfakes are not unprecedented, the panic around the technology is unjustified.

He said: “Making a deepfake isn’t as simple as pressing a button – to create a convincing deepfake requires a significant level of expertise, large image sets of the target and considerable computing power.”

We should instead be thinking about media reform and institutional political change to combat the social problems behind deepfakes, according to his research.

Deepfake pornography has become a huge cause for concern, with celebrities frequently being edited into sexual videos without their consent. As this disproportionately affects women, Dr Habgood-Coote says this form of pornography says more about misogyny than technology.

Dr Habgood-Coote said: “We can see the threat of pornographic deepfakes is not that they persuade anyone that they are a genuine depiction of the target woman... but is rather their ability to effectively spread sexist propaganda.”

We should also be concerned about the effect of deepfakes on racialised groups, according to the research.

For example, a Black ‘virtual influencer’, Shudu Gram, sparked controversy in 2018 after it was revealed that all images of ‘Shudu’ were computer-generated by a white creator, according to the New Yorker. With nearly a quarter of a million Instagram followers, ‘Shudu’ is often shown advertising products for huge brands including Samsung, Louis Vuitton and Fila.

In recent days it has also been announced that Levi’s will begin testing AI-generated models to diversify the shopping experience on its website, showing clothes on models of different body types, ages, sizes and skin tones.

“These examples raise important questions about how deepfakes will be used to fetishise, commodify and dehumanise marginalised groups,” Dr Habgood-Coote said.

Further information

Email University of Leeds Press Officer Mia Saunders at m.saunders@leeds.ac.uk with media enquiries.

‘Deepfakes and the epistemic apocalypse’ by Dr Joshua Habgood-Coote was published in Synthese. DOI: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11229-023-04097-3.

This research is part of a project that has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement no. 818633).

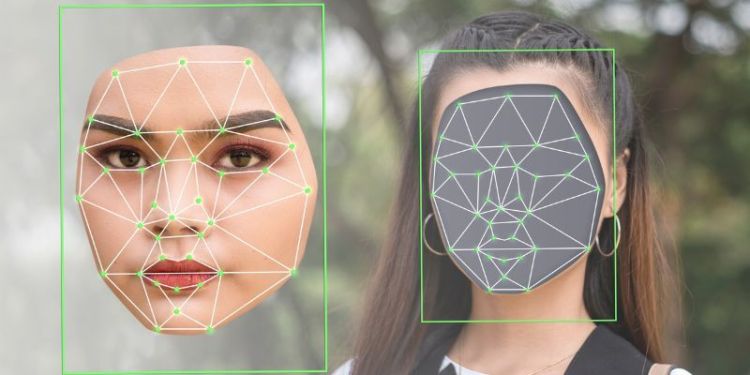

Image: Adobe stock