Frederic Forster's Mourning Warehouse and what to wear to mourn a Queen

The death of Queen Victoria and the need to wear mourning dress meant a booming trade for Leeds’ high street.

While the need to wear black for a set length of time was not part of the nation’s mourning process after the death of Queen Elizabeth II (except perhaps for newsreaders), Victorians faced months of a set dress code.

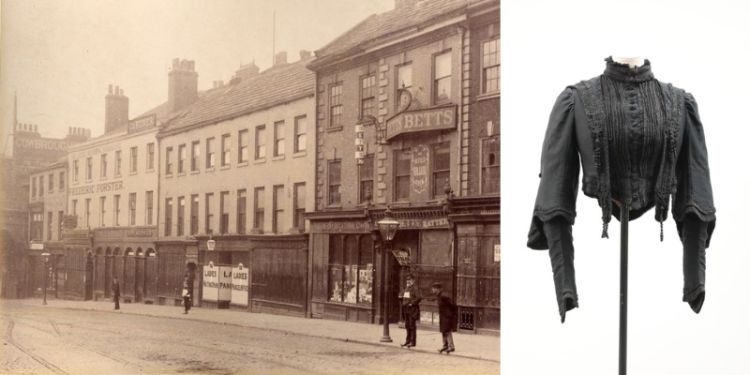

Frederic Forster’s Mourning Warehouse, on Lower Briggate in Leeds city centre, dedicated itself to mourning wear.

The trade dominated the high street in the late 19th century – but why has it now disappeared?

That is the subject of a new research project in the School of Design, led by Associate Professor Kevin Almond, which is examining a collection of items from the Mourning Warehouse held by Leeds Museums and Galleries.

To twenty-first century observers, the idea that the Earl Marshall’s office could tell people what to wear seems shocking.

You can read more about the project in our research directory.

In the piece below, co-investigator Dr Judith Simpson, of the Faculty of Arts, Humanities and Cultures, explains why the Leeds Mourning Warehouse was needed – and the dress code for mourning a queen.

She writes:

When Queen Elizabeth II died, people from all over Britain travelled to London to pay tribute, but they went in their ordinary clothes; in jeans and sports gear.

This forms a striking contrast with the mourning for Queen Victoria in 1901, when the general public were instructed to wear full mourning dress for five weeks and “half mourning” for six.

For men, mourning dress was typically a black tie, hat band and arm band, but women would be expected to wear a matte black dress for the first five weeks and to wear only the mourning shades of black, grey and violet for the following six.

In 1901 Leeds supported a vigorous trade in mourning wear. All drapers stocked it; large stores had dedicated mourning departments and Frederic Forster ran the Leeds Mourning Warehouse on Lower Briggate, where he carried “an immense stock of mourning novelties”.

To twenty-first century observers, the idea that the Earl Marshall’s office could tell people what to wear seems shocking: but the practice of wearing black mourning clothing had strong and varied roots.

The first was the religious tradition of dressing mourners in the coarse dark robes associated with monasticism, in order to maximise prayers for the dead and encourage the living to reflect on their own mortality. For many Victorians some sense that mourning wear fulfilled a spiritual duty persisted.

Outfits that were “novel, handsome and stylish”

Mourning clothing also offered an opportunity to demonstrate personal respectability and compete for social status: when courtiers demonstrated their allegiance to the throne by donning black, commoners would follow suit.

Equally, for the middle-class Victorian, mourning wear was a fashion product. Frederic Forster boasted that he bought stock in London and Paris, was inspired by the latest magazines and sold outfits that were “novel, handsome and stylish”.

The garments from his shop now held by Leeds Museum certainly indicate a concern for elegance and – perhaps – for conspicuous consumption.

However, it remains likely that the Victorians who rushed to buy mourning clothing when their Queen died, were also strongly motivated by the desire to be part of a historic event, to experience a connection with their countrymen and to engage with what Professor Stephen Coleman, writing in The Conversation, has described as “emotionally resonant shared narratives”.

In this respect, the mourners for Queen Victoria and those mourning Queen Elizabeth had a great deal in common.