Research project

Death in Early Modern Venice

- Start date: 24 January 2011

- End date: 31 July 2019

- Funder: Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC), British Academy/Leverhulme Trust, I Tatti: The Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies

- Primary investigator: Dr Alex Bamji

Description

Why did death and the dead matter so much to urban communities?

Focusing on the city of Venice in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, my project evaluates how death was entangled with religious and social change. I address three questions:

- how did people die?

- what did the living do with dead bodies?

- and how did death bring people together?

I explore why certain causes of death provoked anxiety; highlight the materiality of the dead body and its movement through urban space in the transition from deathbed to burial place; and examine the role of family, lay religiosity, and mobility in experiences of death. My research draws on interdisciplinary approaches and emphasises the spiritual power of the laity and the agency of the dead.

Research Overview

Mortality

Around 5,000 people died each year in Venice. While people often think about the impact of epidemic disease like plague, my research draws attention to other important patterns, including the high proportion of deaths of infants and children, and growing numbers of deaths from smallpox. Sudden, accidental, and violent deaths were often recorded in detail.

Bodies

Where people were buried was shaped by lots of factors, including available space; public health concerns; religious belief, status and rules; social status; age; gender; cause of death; and personal preference. My research finds there was a shift to more burials inside churches and looks at the development of public cemeteries.

Death and the urban community

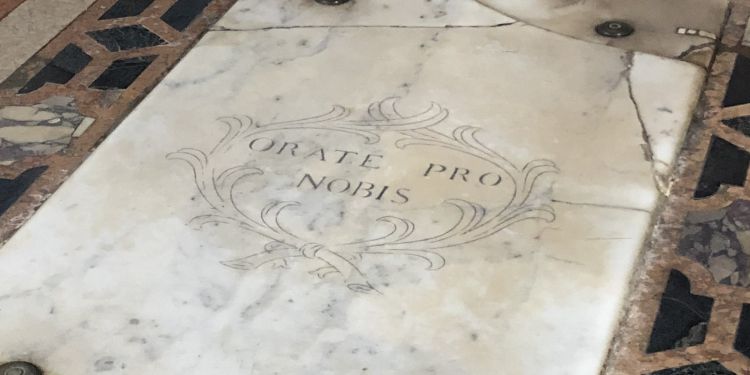

The bonds of family and community included the dead. My research studies the emergence, development, devotional activity, dress, and buildings of a group of new confraternities (lay devotional associations) which focused on death. The many members of these confraternities took part in regular activities in public spaces as well as in their buildings. This made death very visible to everyone going about their daily life in the city.

Publications

Alexandra Bamji, 'Medical care in early modern Venice', Journal of Social History 49:3 (2016): 483–509.

Venice’s Health Office compiled highly detailed civic death registers from the early sixteenth century until after the fall of the Venetian Republic in 1797. This article traces the evolution of recording practices and analyses the information the registers contain, including age at death, gender, social status, and medical care the deceased had received from practitioners and institutions. My research found that recourse to medical care by adults increased to a high level during the seventeenth century and became near-universal by the end of the eighteenth century.

Alexandra Bamji, 'Marginalia and mortality in early modern Venice', Renaissance Studies 33:5 (2019): 808–831.

Some entries in Venice’s civic death registers had a drawing in the margin to the left of the text. These drawings include buildings, daggers, guns, lightning bolts, and waves. This article explores how marginalia enhanced the value of these registers for the people and rulers of early modern Venice. Scribes used visual marginalia regularly and with intent, especially in relation to the deaths of men of working age. Most images were connected to the cause of death, with a lot of interest in accidental, violent, and sudden deaths. The marginalia helped officials to notice deaths which might pose a risk to civic health or social order, and to signpost deaths which might need further investigation. My article argues that handwritten documents remained dominant for bureaucratic purposes because the combination of visual and textual was so powerful and effective.

Alexandra Bamji, 'The materiality of death in early modern Venice', in Religious materiality in the early modern world, ed. by Suzanna Ivanic, Mary Laven, Andrew Morrall (Amsterdam University Press, 2019), pp. 119–135.

This essay examines the complex attitudes of the living to dead bodies, and the role of material objects in the transition from deathbed to burial space. Candles and torches surrounded the body, which might be clothed in a shroud and placed on a catafalque. In the eighteenth century, wax death masks sometimes replaced the physical body of political and religious leaders during funerary rites. My article explores why many of these objects were ephemeral and recycled and highlights the visibility of dead bodies in the city.

Alexandra Bamji, ‘Blowing smoke up your arse: Drowning, resuscitation and public health in eighteenth-century Venice’, Bulletin of the History of Medicine 94:1 (2020): 29–63.

This article studies resuscitation practices in the second half of the eighteenth century, especially the new use of tobacco smoke enema machines on people who had been extracted from the water with no signs of life. Drownings made up a small number and proportion of urban deaths, yet the Venetian government promoted resuscitation techniques at considerable expense in order to prevent such deaths.