Research project

Reform and Clerical Authority: Comparative Perspectives, c. 1000-1200

- Start date: 1 October 2016

- End date: 21 May 2022

- Funder: Leverhulme Trust; Internal funding

- Primary investigator: Dr Maroula Perisanidi

Description

How different should a cleric be from his congregation?

Should a bishop or priest be allowed to hunt, fight, or have sex?

These are questions that preoccupied medieval churchmen whose authority depended on lay people’s willingness to follow clerical advice. To address them, in the 11th century the Western Christian Church underwent a series of reforms which aimed to strictly separate the clerical from the profane. By doing so, it increased its authority as an institution but also affected (not always positively) the personal authority of clerics as men.

However, this was not the only way to gain religious authority. By adopting a comparative perspective, this project investigated how the Byzantine Church dealt with these questions of institutional and gendered authority without undergoing a similar program of reform.

Research Findings

Clerical Marriage

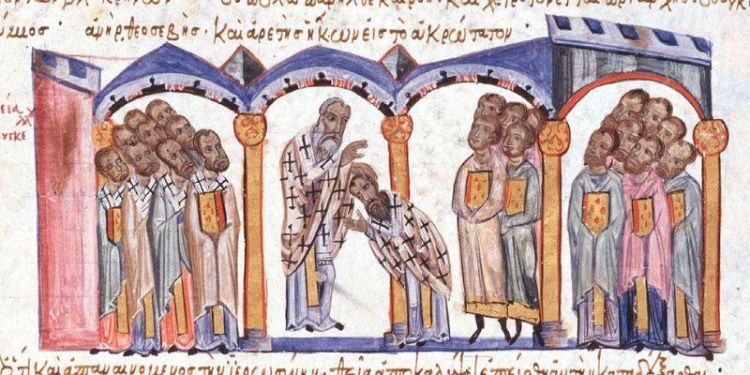

Byzantine priests, deacons, and subdeacons who already had a wife needed to abstain from sex with her temporarily, before their service at the altar. Only Byzantine bishops were expected to observe complete abstinence after their ordination to the episcopate. The rules were much stricter for their Western counterparts, for all of whom there was an expectation of absolute continence.

As this research shows, there are two main reasons that explain these different attitudes of the Western and Byzantine Churches on the topic of clerical continence:

- In Byzantium, sexual abstinence was not linked to fears of ritual pollution. Unlike Western clerics, when Byzantine ones were asked to abstain from sex, it was to avoid being distracted from their duties.

- The way that the Byzantine Church was structured in terms of its finances meant that clerical dynasties did not pose the same risks of property alienation, and as such there was no need to protect against them.

Clerical Violence and Masculinity

Western reforms targeted not only sex but also hunting and fighting, and clerics had to resort to less direct means if they wished to lay claim to certain aspects of secular manhood while adhering to ecclesiastical rules.

The situation was quite different for Byzantine clerics. Although they too were strictly prohibited from fighting, they were allowed to hunt and could be involved in other types of violent activities as long as they did not do so with anger. This research explores the consequences that these differences had for the clerics’ masculinity. It also compares the gender expression of clerics to that of other men, with a particular focus on scholars.

Animals

In this research animals appear in different guises: from “dumb” grazing beasts that act as a foil for the learned man, to emotional support pets who comfort scholars in their illness or keep them company during their studies, to hunted prey and hunting partners. They can be the recipients of scholarly praise, affectionate attention, or bloody violence. As this research shows, which role animals ended up playing on each occasion, and how grievable or worth living their lives were considered, had an impact on the masculine expression of those with whom they interacted.

For example, the use of horses, mules, and donkeys could have significant consequences for the gender of those riding them. In Byzantium, these equids acted as carriers of political and gender rhetoric, and as their social and religious connotations interacted with the social and religious status of their riders, they had the potential to masculinise or emasculate. These connotations also had real consequences for the animals themselves. As this research shows through narratives of humiliation parades, we can use modern veterinary science to shed light on the animal’s bodily experience.

Funding

From 2016-19, this research was funded by a Leverhulme Trust Early Career Fellowship. From 2019-22, this research was supported by the University of Leeds.

Outputs

Books

Articles and Chapters

- ‘Teaching Monastic Masculinity with the Colloquy of Ælfric of Eynsham’, Early Medieval Europe, 31:4 (2023), pp. 629-49. Available open access through the journal’s website.

- ‘Religious Masculinities in William of Newburgh’s Historia rerum Anglicarum’, Historical Research 96.273 (2023), pp. 283-97. Available open access through the journal’s website.

- ‘Byzantine Parades of Infamy through an Animal Lens’, History Workshop Journal, 90 (2020), 1-25. Available open access through the White Rose Research Online repository.

- co-authored with Dr Oliver Thomas, ‘Homeric Scholarship in the Pulpit: The Case of Eustathius’ Sermons’, Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies, 63.2 (2021), pp. 81–94. Available open access through the journal’s website.

- ‘Eustathios’ Life of a Married Priest and the Struggle for Authority’, in Authority, Power and the Medieval Church, ed. T.W. Smith (Brepols, 2020), 279-88.

- ‘Zonaras’s Treatise on Nocturnal Emissions: Introduction and Translation’, Nottingham Medieval Studies, 62 (2018), 33-59. Available open access through the White Rose Research Online repository.

- ‘Anglo-Norman Canonical Views on Clerical Marriage and the Eastern Church’, The Bulletin of Medieval Canon Law, 34 (2017), 113-142. Available open access through the White Rose Research Online repository.